Part 1: How We Got Here

To understand how the Democratic Party can win again, we must understand how our party arrived at this point.

The Democratic Party has moved to the left since 20121.1

Since Barack Obama's successful reelection campaign, the Democratic Party has moved left on essentially every issue.1 The simplest way to demonstrate this shift is to look at the change in the share of Democratic members of Congress who cosponsored pieces of progressive legislation.

As the table below shows, between 2013 and 2023, the share of cosponsors for progressive legislation increased substantially.2

The Republican Party changed between 2012 and 20241.2

Between 2012 and 2024, Republicans became more extreme on issues like democracy, the rule of law, immigration, and transgender rights. But Republicans also moved toward the center on several issues, including moderating their stances on Medicare and Social Security and dropping pledges to repeal the Affordable Care Act, ban abortion nationwide, and pass a constitutional amendment to prohibit same-sex marriage.3,4

Voters' perceptions of the two parties have changed since 20121.3

Voters have noticed the Democratic Party's shift to the left. Per available public polling, the share of voters who see the Democratic Party as "too liberal" has increased significantly since 2012.

By contrast, during the 2012-2024 period, the share of voters who saw Republicans as "too conservative" decreased.

Since Trump's second inauguration, the share of voters who think the Republican Party is "too conservative" has increased substantially—likely in response to policy overreach by Trump and congressional Republicans. While this presents a major political opportunity for Democrats, our party has yet to capitalize on it. Per the most recent public polling on the topic—a survey from The Washington Post/Ipsos in September 2025—the share of voters who think the Democratic Party is "too liberal" (54%) remains substantially higher than the share of voters who think the Republican Party is "too conservative" (49%).

Democrats have changed what we focus on1.4

In comparison with the Democratic Party of 2012, today's Democratic Party is more focused on issues like climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural concerns and less focused on the economy and the middle class. The table below shows this shift, through an analysis of the prevalence of select words in the 2024 Democratic Party platform, in comparison with the 2012 Democratic Party platform.5

What is driving the shift in the Democratic Party's priorities?

As we will see in more detail in Part 3, highly educated Democratic voters and affluent Democratic voters care more than the average American about issues like climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues—and less than the average American about issues like the cost of living, gas prices, border security, and crime.

Voters think Democrats prioritize the wrong issues1.5

As our party has shifted what we focus on, the share of voters seeing the Democratic Party as "out of touch" has increased dramatically. At the same time, the share of voters who see the Republican Party as "out of touch" has decreased slightly. The result is that more voters say the Democratic Party is out of touch than say the same about the Republican Party.

In addition, per the Democratic polling firm Navigator Research, only 39% of voters say the Democratic Party has the right priorities, while 59% of voters say Democrats do not.

To examine which issues are driving voters' perception that Democrats do not share their priorities, Deciding to Win conducted two surveys. First, we asked voters how much they thought the Democratic Party should prioritize a variety of issues. The results of our first survey are presented in the table below.

Next, we asked voters how much they thought Democrats currently prioritize each of those issues.

We then measured the difference between how much voters thought Democrats should prioritize each issue and how much they thought Democrats do prioritize each issue. The table below shows the results of this analysis.

These results are corroborated by post-election polling from The New York Times, which found that while 47% of voters named the economy as one of their top three priorities, just 17% believed the economy was one of the Democratic Party's top three priorities.6

These results tell a clear story. Voters see Democrats as insufficiently prioritizing issues like the cost of living, the economy, immigration, health care, taxes, and crime, which are all top concerns for voters. At the same time, voters see Democrats as putting too high a priority on climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues.

Going forward, it will be critical for our party to reduce the gap between what voters want Democrats to focus on and what voters think we do focus on. This will likely require making issues like the cost of living, the economy, health care, border security, and reducing crime a higher priority for our party—both in our communications and in our approach to governance—and placing less emphasis on issues like climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues.

Joe Biden governed from the left—and voters noticed1.6

While Joe Biden was not the favored choice of progressives in the 2020 Democratic primary, as president he embraced progressive positions on most issues. And between when Biden was inaugurated and when he left office, polling shows that the share of voters seeing Biden as "too liberal" skyrocketed.

Recent losing Democratic presidential nominees were seen by a majority of voters as too liberal1.7

The table below shows, per the average of available public polls for each election, the share of voters who thought the Democratic presidential nominee was "too liberal."

As the table shows, in the two most recent elections Democrats lost, a majority of voters saw the Democratic nominee as "too liberal." By contrast, in the two most recent elections Democrats won, a majority of voters saw the Democratic nominee as either "about right" or "too conservative."

Democrats have lost significant support among working-class and minority voters1.8

Support for Democrats has declined significantly among working-class and minority voters since 2012. The table below shows these shifts, per data from Catalist.

Places where race and class intersect have seen particularly large declines in Democratic vote share. In Starr County, Texas, for example—a county where more than 95% of residents are Hispanic and the poverty rate is triple the national average—Democratic vote share declined from 86% in 2012 to 42% in 2024. Similarly, the only voting district Trump won in Manhattan was a precinct that solely contains a large affordable housing project, whose residents are overwhelmingly Chinese American and which had previously been solidly Democratic.

Declines in Democratic support have been concentrated among moderate and conservative voters—and particularly among moderate and conservative working-class and minority voters1.9

Overall Democratic vote share in the 2024 presidential election was 2.8 percentage points lower than in 2012. But declines in Democratic support between 2012 and 2024 were not uniform. Democratic losses have been driven by declines among voters who identify as moderate or conservative.7

In addition, declines in Democratic support among working-class and minority voters have been disproportionately driven by declines in support among working-class and minority voters who identify as moderate or conservative.

The disproportionate declines in support among moderate and conservative working-class and minority voters suggest that our party's shift to the left since 2012 has contributed to our losses among these groups.

America's political institutions are biased against Democrats1.10

Democrats need to get more than just 50% of the national popular vote to win congressional majorities, putting pressure on our party to appeal to voters in states that are to the right of the nation as a whole.

The situation is particularly dire in the Senate, where 48 senators sit in states that Donald Trump won by 10% or more in 2024 and where the median seat is 2.8% to the right of the nation as a whole.

Falling ticket-splitting rates have exacerbated Democrats' electoral problems, particularly in the Senate1.11

Support for Democratic congressional candidates in Senate and House races has become dramatically more correlated with presidential results in recent years. More than ever before, Democratic candidates' fortunes in difficult states and districts rise and fall with the national party brand—meaning that improving the national brand as a whole is critical.

Democrats have gone from being the party of sporadic voters to the party of high-propensity voters1.12

Democrats now tend to do better in special elections and midterms, when fewer people vote, and worse in higher-turnout races—a major change from 12 years ago. In 2024, for example, reputable analyses generally found that nonvoters were more supportive of Trump than the general electorate—meaning that if every registered voter had voted, Trump's win would have been larger, not smaller.

Source: The New York Times

Young voters swung heavily toward Republicans in 20241.13

In 2024, young voters—and particularly young men—supported Trump at far higher rates than they had supported previous Republican presidential nominees. The swing of young voters toward Trump should disabuse Democrats of the notion that demographic change will inevitably lead to Democratic victory—and should underscore how important it is to fix our party's brand going forward.

Key takeaways from Part 1:

-

Democrats have moved to the left since 2012 on essentially every issue.

-

Democrats have also changed which issues we emphasize, putting less emphasis on the middle class and the economy and more emphasis on climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues.

-

As we have shifted our positions and our priorities, voters have increasingly come to see our party as too liberal, insufficiently focused on the economy, border security, and crime, and overly focused on climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues.

-

More voters now think the Democratic Party is too liberal than think the Republican Party is too conservative—a significant shift from 2012 to today.

-

All of these changes have corresponded with declines in Democratic support among moderate and conservative voters—evidence that our party's shift to the left has cost us electorally.

-

These declines have been particularly large among moderate and conservative working-class and minority voters—suggesting that doubling down on moving left is not the right approach to winning these voters back.

Part 2: The Electorate

In order to win elections, the democratic party needs an accurate understanding of the American electorate.

The demographics of the electorate2.1

Most voters are white, most voters are non-college-educated, and most voters are over the age of 50.

The ideological makeup of the electorate2.2

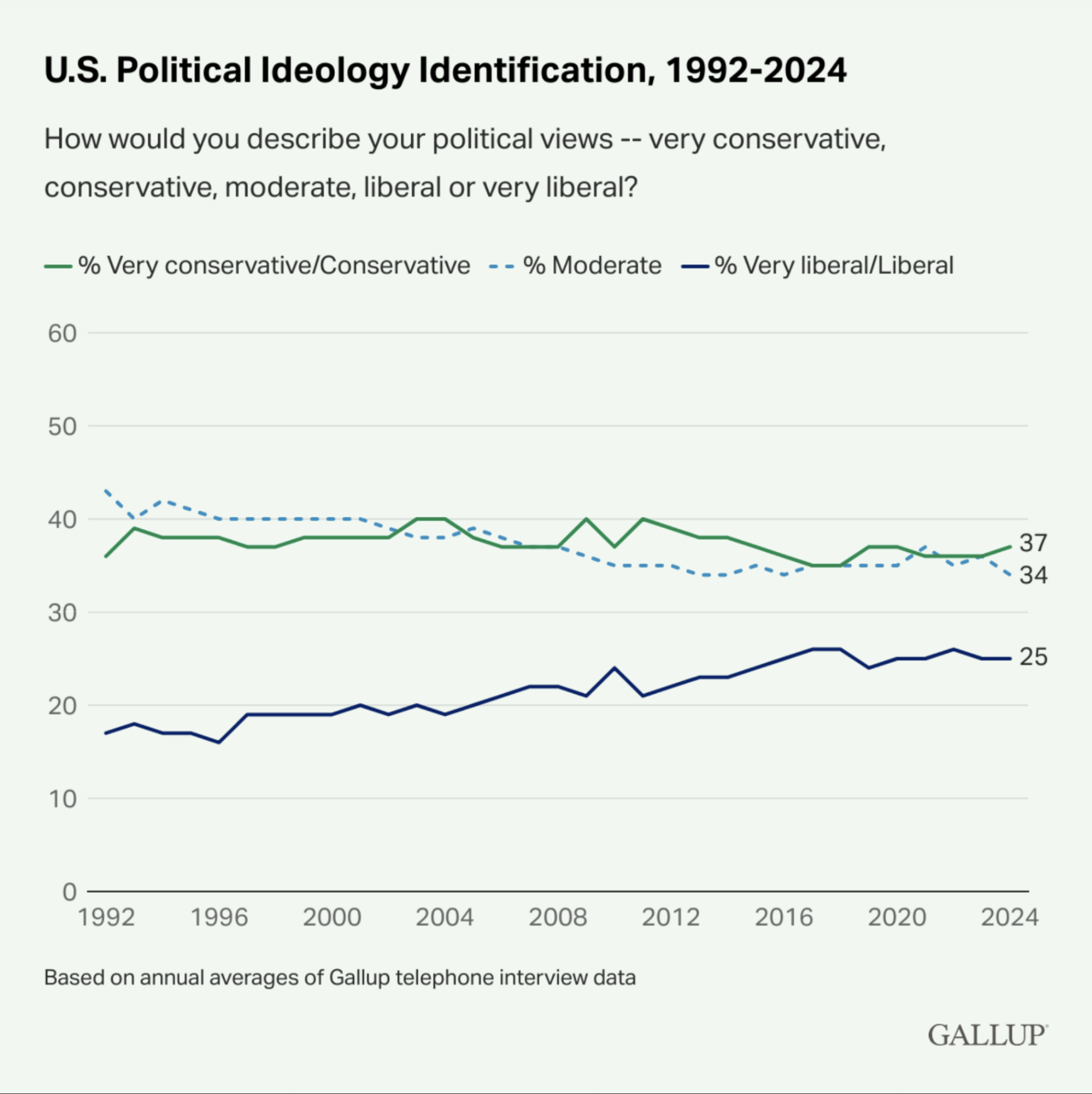

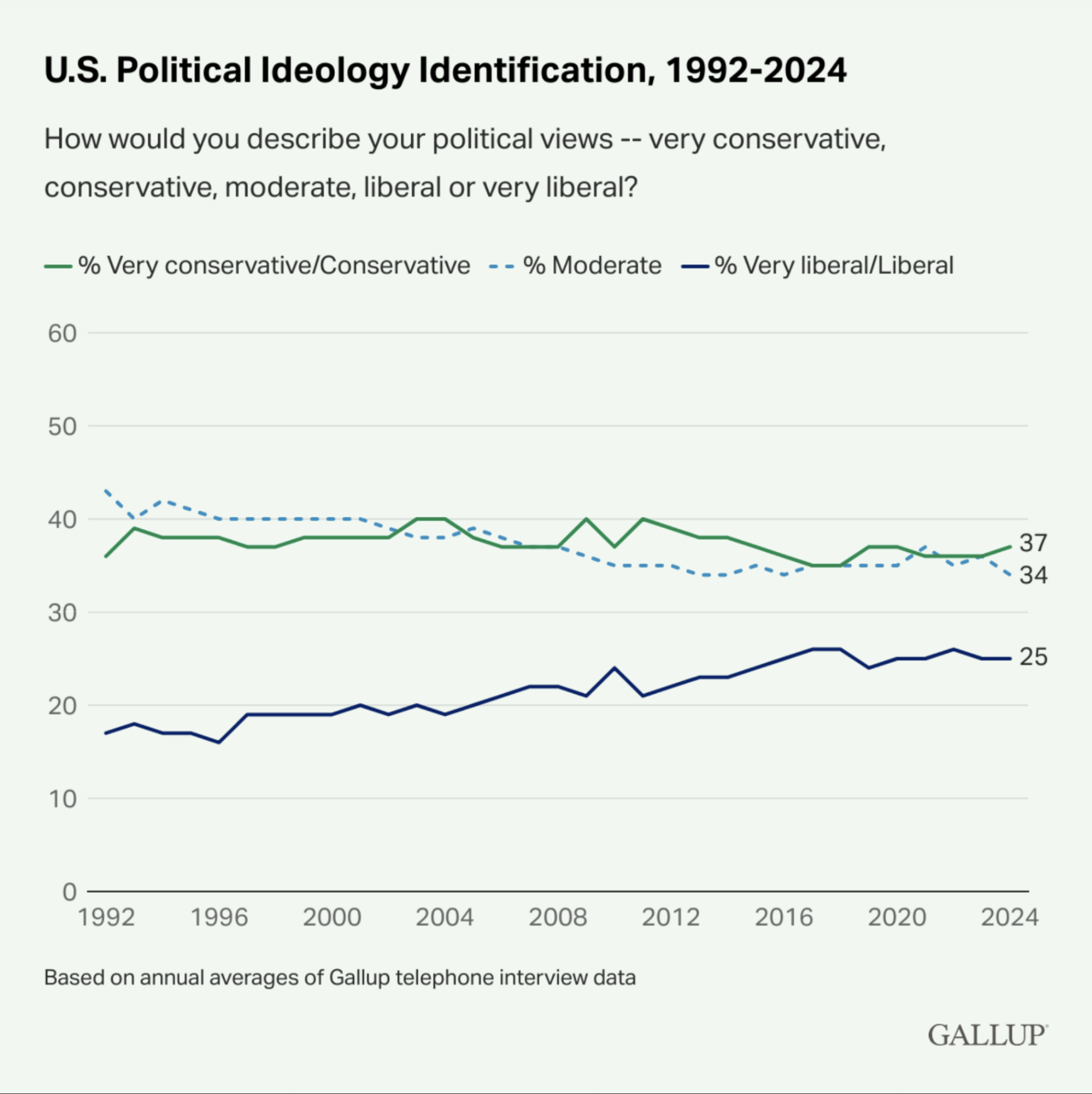

A supermajority of Americans (71%, per Gallup) identify as moderate or conservative, including majorities of swing voters, nonvoters, working-class voters, and minority voters.8

The electorate's views on abstract questions2.3

On a number of philosophical questions, including on taxation, regulation, the role of government, and immigration, majorities of voters hold moderate or conservative views.

The electorate's views on institutions and ideals2.4

Most voters have favorable views of institutions and ideals such as the police, the military, capitalism, small businesses, and America, and unfavorable views of socialism.

Working-class voters vs. college-educated voters2.5

Working-class voters are more conservative than college-educated voters on both social issues and economic issues.

Key takeaways from Part 2:

- The moderate and/or conservative inclinations of the electorate on a number of important questions underscore the difficulties that Democrats' shifts to the left have created for our party.

Part 3: The Forces Within the Democratic Party

In Part 1, we saw how the Democratic Party has changed in recent years. Part 3 helps us understand which groups within our party drove these shifts. We examine how the views of different groups within the Democratic Party differ from each other and from the electorate overall.

Highly educated Democrats in comparison to less well-educated Democrats3.1

Highly educated Democrats are more likely than non-college-educated Democrats to identify as liberal. Younger Democrats are also more liberal than older Democrats, and white Democrats are more liberal than non-white Democrats.

Highly educated Democrats also hold more liberal views than working-class Democrats on both economic and social issues—and see economic issues as relatively lower priorities.

Similar differences in issue prioritization exist between affluent Democrats and lower-income Democrats, with the former seeing issues like political division and climate change as relatively more important and the latter placing a higher priority on issues like poverty, unemployment, Social Security, and gas prices.

Democratic staffers in comparison to Democratic voters and the electorate overall3.2

Academic research shows that Democratic campaign staffers are to the left of Democratic voters, making them even further to the left of the electorate overall. Democratic campaign staffers are also, on average, younger, more highly educated, more likely to be white, more likely to be female, and less likely to attend church than both Democratic voters and the overall electorate.

Democratic Party donors and elites in comparison to Democratic voters3.3

Some argue that Democrats are pulled to the center by our donor class. But academic research shows that both large and small Democratic donors are more left-wing than Democratic voters overall. In addition, research from Data for Progress shows that Democratic elites are significantly to the left of the general public, and that the gap between Democratic elites and the public is larger than the gap between Republican elites and the public. Ultimately, large Democratic donors, small Democratic donors, Democratic campaign staffers, and Democratic elites all likely act to pull our party to the left overall—not to the center.

Highly educated Democrats and affluent Democrats in comparison to working-class voters, swing voters, and the general electorate3.4

In comparison to working-class voters, swing voters, and the general electorate, highly educated Democrats assign significantly greater importance to issues like climate change, guns, political division, voting rights, and income inequality, and significantly less importance to issues like border security, immigration, crime, gas prices, and the budget deficit.

The table below shows these differences based on polling we conducted. Positive numbers indicate issues that highly educated Democrats prioritize more, while negative numbers indicate issues that highly educated Democrats prioritize less.

The results are similar when we look by income. Democrats who make more than $150,000 a year place a higher priority on issues like climate change (+23%), guns (+17%), and income inequality (+11%) in comparison to the average voter. At the same time, wealthier Democrats place a lower priority than the general electorate on issues like border security (-27%), crime (-13%), and gas prices (-10%).

These differences suggest that the significant—and growing—influence of highly educated and affluent voters on the Democratic Party's agenda and message may be responsible for the Democratic Party shifting its priorities away from more salient, material issues (as we saw in Part 1), as well as for voters' perceptions that Democrats are not focused on the right issues.

These results also indicate that increasing the influence of working-class voters on the Democratic Party's agenda and message would likely mean making issues like crime, gas prices, border security, and the cost of living a higher priority and making issues like political division, guns, climate change, and voting rights a lower priority.

Progressive advocacy groups in comparison to working-class and minority voters3.5

Highly educated white voters tend to be more liberal than working-class white voters. Highly educated minority voters also tend to be more liberal than working-class minority voters. This introduces the potential for disconnects between progressive advocacy organizations, which are generally run by highly educated staff, and the groups whose interests they aim to advance, who are predominantly working-class. Democratic elected officials would do well to keep in mind that the policy preferences of progressive advocacy groups may not always represent the preferences of the communities that these groups advocate for.

Democratic voters care deeply about winning elections3.6

In the 2020 Democratic primary, polls consistently found that Democratic primary voters prioritized electability over ideology—a lesson for 2028 Democratic hopefuls.

Key takeaways from Part 3:

-

Large Democratic donors, small Democratic donors, Democratic campaign staffers, Democratic elites, highly educated and affluent Democratic voters, and progressive advocacy groups all pull the Democratic Party to the left—and push our party to prioritize climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues at the expense of kitchen-table issues like the cost of living.

-

Meanwhile, Democratic voters deeply want the party to win.

Part 4: The Myth of Mobilization

Some Democrats argue that to win, our party should move left to mobilize our base. This section examines mobilization theory in detail and finds that it gets things backward. In fact, more progressive Democrats tend to do worse electorally, while more moderate Democrats tend to do better. The same is true for more moderate Republicans, who tend to outperform more conservative Republicans.

In House and Senate races, moderate Democrats tend to outperform electoral expectations, while progressive Democrats tend to underperform. The table below illustrates this trend in 2024 House races.9

What do we mean when we use the term "moderate"?

• We DO mean: Taking popular positions on the issues voters care most about; breaking with Democratic orthodoxy on issues like immigration and public safety where the mainstream Democratic position is unpopular.

• We do NOT mean: Reflexively defending the status quo, the establishment, or corporate interests—or always taking the centrist position, even when that position is unpopular.

In other words, "moderation" means taking popular, often heterodox positions. Skip ahead to Part 8—"What It Does and Does Not Mean to Be Moderate"—for more detail.

Moderate Republicans also tend to outperform electoral expectations, while conservative Republicans tend to underperform.

Looking at both parties together, the picture becomes clear. More moderate candidates tend to do better electorally, while more progressive Democrats and more conservative Republicans tend to do worse.

Per available public polling data since 1960, presidential candidates who are perceived as more moderate have tended to do better electorally.

A review of the academic literature on the electoral impact of being more moderate4.5

Recent academic literature on the effects of ideological moderation on electoral outcomes largely corroborates our findings above: More extreme candidates pay an electoral penalty, while more moderate candidates perform better, particularly in races for executive offices and in higher-salience elections.

The relative impact of turnout and persuasion in recent national elections4.6

The effects of changes in how people vote (persuasion) and the effects of changes in which people vote (turnout) tend to point in the same direction—but the effects of persuasion are usually larger.

Swing voters are real4.7

Yes, swing voters exist—and in close elections, they are often the difference between winning and losing.10

Vote switching from election to election is often associated with issues4.8

Evidence suggests that changes in voter preferences from election to election are often correlated with voters' views on issues as well as which issues are salient in a given campaign.

Turnout rates for demographic subgroups tend to move in unison from election to election4.9

Turnout rates differ by demographic subgroups. But the turnout rates of demographic subgroups tend to increase and decrease in unison from election to election.11 This dynamic suggests that campaigns struggle to increase turnout among specific, favorable demographic groups. Further, as described in Part 1.12, Democrats are now the party of high-turnout voters, meaning that generalized increases in turnout among all groups are more likely to benefit Republicans than Democrats.

Canvassing, phone banking, and other campaign interventions can't and won't save us4.10

Academic research shows that field programs like canvassing and phone banking have minimal impacts on changing voters' minds and small impacts on increasing voter turnout.12 Ultimately, there is little evidence to suggest that our party will be able to overcome its problems by knocking on more doors. If we cannot persuade voters with our policy agenda and message, we are unlikely to be able to win via our "ground game."

Part 4 also looks at the differences and similarities between the voters Democrats need to persuade and the voters we need to turn out.

How moderate voters differ from liberals and conservatives4.11

Academic research shows that voters who have consistently liberal or conservative views are less persuadable than both voters with consistently moderate views and voters with a mix of liberal and conservative views.

How Democrats who vote sporadically differ from Democrats who vote consistently4.12

In policy polling we conducted (discussed in more detail in Part 5), we found that the voters Democrats lost "to the couch" in 2024—those who backed Biden in 2020 but did not vote in 2024—had more moderate policy preferences than those who voted for Biden in 2020 and Harris in 2024. In other words, Democratic-leaning voters who vote sporadically tend to be more moderate than Democratic voters who vote consistently.13

The false trade-off between persuasion and mobilization4.13

Support for current and past Democratic Party policies among swing voters is highly correlated with support among infrequent voters. As the chart below shows, for more than one hundred Democratic policies we polled, there is a strong positive relationship between policy support among 2024 swing voters (horizontal axis) and policy support among 2024 nonvoters (vertical axis). Popular policies are popular with swing voters and nonvoters, while unpopular policies tend to do poorly with both groups.

For example, expanding prescription drug negotiation—a longtime priority of Senator Bernie Sanders—has more support among the general electorate than 98% of Democratic policies we polled and is above the 95th percentile of support among both swing voters and nonvoters. By contrast, increasing the number of refugees allowed to come to the United States each year is in the 8th percentile of support with the general electorate relative to all Democratic policies we polled—and is below the 10th percentile of support among both swing voters and Democratic get-out-the-vote targets.

The persuasive effects of political messaging are also highly correlated between swing voters and nonvoters—as are which issues nonvoters and swing voters prioritize.

These results imply that there is no trade-off between a platform, message, and set of priorities that appeal to the voters Democrats need to persuade and a platform, message, and set of priorities that appeal to the voters Democrats need to turn out.

Correlations in policy support among other groups4.14

Policy support is also highly correlated between other groups, such as white voters and nonwhite voters, young voters and older voters, and women and men.14 In other words, tailoring messaging or policies to appeal to specific demographic groups is generally unnecessary.

After mobilization theory4.15

Our party needs to move on from mobilization theory and acknowledge that focusing on appealing to our most fervent supporters is not the best path to electoral success. Instead, we need to focus on winning over voters in the middle, many of whom have supported Democrats in the past and could again if our party had a more appealing agenda, set of priorities, and message.

Key takeaways from Part 4:

-

Progressive Democrats often argue that to win, Democrats should move left in an attempt to "mobilize our base."

-

However, the data shows that progressive Democrats underperform moderate Democrats electorally, swing voters exist and are often decisive, and sporadic Democratic voters are more moderate than Democrats who vote consistently.

-

Ultimately, persuasion and turnout go together. Voters across the political spectrum and across demographic lines want Democrats to focus on the cost of living. And the best messaging and most popular policies—which tend to focus on kitchen-table economic issues—appeal to voters of all kinds, including both swing voters and sporadic voters.

Part 5: What Is Popular and What Is Not

To see where Democrats should go from here, we need to understand which policies are popular and which are not. This section examines why traditional issue polling is broken—and what more methodologically sound issue polling shows about which parts of the Democratic agenda are popular.

Why traditional issue polling is broken5.1

Academic research comparing ballot initiative results to issue-polling averages shows that traditional issue polling—of the kind conducted by advocacy groups—substantially overstates support for liberal policies.15

A better way to do issue polling5.2

We employ a different issue-polling methodology (described in detail here that we believe provides more accurate estimates of support for Democratic and Republican policies—even if this approach presents a less rosy picture for parts of the Democratic agenda.

Trust and salience5.3

Before looking at our issue polling results, we first examine the results of trust and salience polling we conducted.16 We find that:

-

Issues like the cost of living, the economy, inflation, taxes and government spending, and health care are most important to voters.

-

Democrats face trust deficits on most of the issues that are high priorities of the electorate, including the economy, the cost of living, and inflation. Democrats face particularly large trust deficits on issues like border security and crime.

By contrast, issues where Democrats are trusted more—like climate change, abortion, and LGBTQ issues—tend to be less important to voters.

Our polling also shows that foreign policy issues are of low importance to voters, with "War in the Middle East" ranking as the 30th most important issue to the electorate overall (out of 36 issues we tested), and "The War in Ukraine" ranking as the 34th most important issue.17

Contextualizing our issue polling5.4

We provide additional context and nuance for understanding our issue polling results. We encourage readers to look at the full wording of each of the policies we polled in order to best understand our results.18

Issue polling results5.5

Overall, we find that the most popular parts of the Democratic policy agenda center on protecting and expanding health care access, defending Social Security and Medicare, making the wealthy pay their fair share in taxes, and protecting abortion rights.

But while many Democratic policies are popular, roughly half of the Democratic policies we polled are unpopular. Unpopular Democratic policies tend to be progressive proposals on immigration and crime, proposals to restrict energy production, and proposals to create large new social programs that voters do not see as top priorities.

The most unpopular Republican policies tend to be cuts to health care and entitlement programs and proposals to restrict reproductive rights.

However, roughly half of the Republican policies we polled had majority support. Popular Republican policies tend to focus on stricter approaches to border security and crime, as well as lowering taxes, increasing energy production, and conservative positions on some identity and cultural issues.

We polled 190 policies in total—105 Democratic policies and 85 Republican policies. Support for the Democratic policies was 49.3% on average, while support for the Republican policies was 50.4% on average.

The average support for the Democratic position—the affirmative side for the Democratic policies and the negative side for the Republican policies—across all 190 policies we polled was 49.4%. It is notable that this figure is remarkably close to the overall share of the vote that Kamala Harris received in the 2024 election (49.2%). While this does not prove anything, it does offer an indication that our methodology and results are connected to real-world public opinion.

The tables above present select results from our policy polling. Our full policy polling results can also be viewed by issue area, including Health Care, Taxes, Other Economic Policies, Immigration, Crime, Policing, and Criminal Justice, Tariffs, Climate and Energy, Reproductive Rights, K-12 Education, Higher Education, Family Policy, Democracy Reforms and Voting Rights, LGBTQ Issues, DOGE, Artificial Intelligence, Abundance, and Other Policies.

Putting the whole picture together5.6

A clear picture emerges from combining the results of our issue polling, trust polling, and salience polling.

First, Democrats need to focus on our popular positions on high-salience issues. This means protecting and expanding Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security, fighting against tax cuts for the rich, and opposing Trump's tariffs. It also means putting forward an economic agenda that will help working-class Americans, including policies like expanding prescription drug price negotiation, ensuring the wealthy pay their fair share in taxes, raising the minimum wage, expanding Medicare to cover dental, vision, and hearing, and making school lunch free for all students.

Second, Democrats need to affirmatively moderate our positions on high-salience issues where voters distrust us and where progressive policies are unpopular, particularly on immigration, crime, and energy policy. These issues are important to voters, and simply hoping we can avoid talking about them is unlikely to work. If we continue to advocate for unpopular policies on these issues, they are likely to continue costing us electorally.19

Third, Democrats should continue to staunchly support popular progressive positions on lower-salience issues, with defending reproductive rights the most prominent issue in this category.

Fourth, Democrats should shift our stances on some lower-salience issues where our views are unpopular, including some cultural concerns (e.g., affirmative action in college admissions, transgender athletes). Democrats should also focus less on these lower-salience cultural issues and focus more on the economy and the cost of living.

Finally, while we do find that some Democratic policies are unpopular, it is worth emphasizing that our results provide much for all factions of the Democratic Party to be enthusiastic about. Policies like raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour; protecting abortion rights nationally; expanding prescription drug price negotiation; returning power over tariffs to Congress; closing tax loopholes for the wealthiest Americans; banning partisan gerrymandering; banning discrimination against LGBTQ Americans in housing and employment; investing in reducing lead pollution; cracking down on estate tax evasion; expanding Medicare to cover dental, vision, and hearing; increasing Social Security benefits for low-income seniors; and establishing universal free school lunch are all supported by a clear majority of Americans. A Democratic administration that was able to enact all of these policies would represent a massive success and a major victory for the progressive movement.

Key takeaways from Part 5:

-

Traditional issue polling significantly overestimates support for progressive policies.

-

In reality, Democrats have a mix of popular positions (e.g., on health care, Social Security, and reproductive rights) and unpopular positions (e.g., on immigration, crime, energy policy, and some identity and cultural issues).

-

We need to focus on our popular positions, particularly on health care and the economy, while moderating our unpopular positions, particularly on immigration and crime.

-

A Democratic agenda focused only on the most popular Democratic policies would feature much for both moderate and progressive Democrats to be excited about.

Part 6: What Candidates Do and Say Matters

As the impact of inflation on the 2024 election made clear, the state of the economy is likely the single most important factor in how the incumbent president's party does electorally. But the economy isn't the only thing that influences elections.

Substantive positioning affects electoral outcomes6.1

In recent years, a "vibes"-based theory of politics has emerged, claiming that election results have little or nothing to do with the substantive positions of the candidates on public policy issues. This section provides evidence that substantive positioning does affect electoral outcomes.

In the table below, we look at the relationship between what stances House Democratic incumbents take and how they perform electorally. We find a clear relationship—incumbent Democratic candidates with more moderate positions on the issues tend to overperform electorally, while Democratic incumbents with more progressive positions tend to underperform. We find that this relationship also holds for House Republican incumbents, as well as for both parties in the Senate. We also find—for both parties in both chambers—that candidates who more frequently take moderate positions tend to do better electorally.

A significant body of academic research corroborates the findings in the table above.

Substantive positioning affects how candidates are perceived6.2

We conducted a large-scale study to determine where voters perceived every 2024 House candidate to fall on a left-right ideological spectrum.20 The results of our study demonstrate that substantive positioning is correlated with voters' perceptions of candidates' ideologies. We find that Democrats with more moderate positions on the issues are perceived as more moderate, while Democrats with more liberal positions are perceived as more liberal. Similarly, Republicans with more moderate positions are perceived as more moderate, and Republicans with more extreme positions are perceived as more conservative.

Case studies on the electoral impact of substantive positioning6.3

Case studies of politicians who have shifted their positions over time—including Bernie Sanders, Tim Walz, and Joe Biden—illustrate the connection between substantive positioning and electoral performance/voter perceptions.

Understanding how and why substantive positioning impacts electoral outcomes6.4

We present a model for understanding the mechanisms by which substantive positioning affects election outcomes based on the evidence in Parts 6.1-6.3.

Key takeaways from Part 6:

-

There is strong evidence that candidates' substantive positions—their voting record, their positions on the campaign trail, their governance decisions while in office—affect their electoral performance.

-

How voters perceive candidates matters—but perceptions are influenced by substantive positioning, not divorced from it.

Part 7: What the Strongest Democratic Candidates Talk About

To understand what political messaging and issue positioning is most effective for Democrats, a good starting point is the messaging used by Democrats in swing districts, particularly those Democrats who overperform. These are the candidates with the least margin for error and the clearest incentive to run on the strongest platform possible.

Our analysis of ads from some of the strongest frontline Democratic candidates shows that they tend to focus their paid media on themes of pragmatism, economic priorities, and messaging that breaks with progressive orthodoxy on issues like immigration, crime, and energy production, as well as popular positions on issues like health care, border security, and reproductive rights.

As our party looks to rebuild and form a national electoral majority going forward, the approach of representatives like Jared Golden or senators like Ruben Gallego should be our starting place.

Republicans who significantly overperform electorally also tend to emphasize bipartisanship and moderate positions on issues like health care and Social Security.

Nebraska Senate case study7.3

Independent Nebraska Senate candidate Dan Osborn attracted significant attention due to his strong electoral performance relative to the partisanship of the state. While Osborn ran on anti-elite rhetoric and some left-wing policies, he also took conservative positions on a number of important issues, most notably immigration.21

Key takeaways from Part 7:

-

To figure out what messaging is most effective, we should look at the Democratic candidates who most overperform the national ticket.

-

These Democrats mostly run on economic messaging, themes of bipartisanship and pragmatism, and popular policies, including breaks from progressive orthodoxy on issues like immigration, crime, and energy policy.

Part 8: What It Does and Does Not Mean to Be Moderate

Throughout this report, we argue that Democrats should moderate. In this section, we take a closer look at exactly what it means to be a "moderate," including how being a moderate interacts with being an outsider and/or a critic of the establishment.

Being moderate means taking popular, heterodox positions—not defending the establishment8.1

Voters express substantial skepticism of the status quo, the establishment, and political elites. Large swaths of the electorate think the system is rigged against people like them and in favor of the wealthy. A supermajority of voters thinks it is more important to have a candidate who delivers change that improves people's lives than to have one who preserves institutions as they are today.

None of this is in tension with earlier sections of this report. Running as an outsider or as a critic of the establishment is not only compatible with campaigning as a moderate, but is often complementary.22 In our view:

-

Being moderate means taking popular positions on issues that are important to voters and being willing to break with one's party on issues where the party orthodoxy is unpopular.

-

Being moderate does not mean running on a defense of the political establishment, elites, corporate interests, or the status quo. It also does not mean having a mild-mannered temperament or taking the centrist position on every issue.23

Disentangling "moderation" and "defending the establishment," however, still leaves open the question of whether Democrats ought to be more critical of the political establishment, to lean into anti-elite sentiment, and/or to nominate an outsider in 2028. In our view, the case for a more anti-establishment posture is strong—with a few important caveats:

First, anti-establishment rhetoric can't fix problems caused by unpopular position-taking: Democratic candidates who criticize the establishment but run on unpopular positions on issues that are important to voters, like immigration or public safety, tend to be poor electoral performers.24 Ultimately, anti-establishment rhetoric is a complement to a popular policy agenda, not a substitute for it.

Second, younger candidates won't solve all our problems: There are good reasons to think the Democratic Party would benefit from older elected Democrats passing the torch more quickly. But merely making the Democratic Party younger is not a panacea. An infusion of youth should complement substantive repositioning and a shift in prioritization, not substitute for it.

Third, frustrations with the status quo are not the same as a desire for socialism: While many voters feel frustrated with the status quo and their economic situation, large majorities of Americans continue to have positive views of capitalism, and large majorities continue to have negative views of socialism.

As Democratic Senator Ruben Gallego—who significantly overperformed in his 2024 Arizona Senate race—explained in a post-election interview with The New York Times about what Democrats get wrong about working-class and minority voters:

These people want to be rich. They want to be rich! And there's nothing wrong with that. Our job is to expose when there are abuses by the rich, the wealthy, the powerful. That's how we get those people that aspire to that to vote for Democrats...

We're afraid of saying, like, "Hey, let's help you get a job so you can become rich." We use terms like "bring more economic stability." These guys don't want that. They don't want "economic stability." They want to really live the American dream...

People that are working-class, poor, don't necessarily look at the ultra-rich as their competitors. They want to be rich someday. And so they don't necessarily fault the rich for being rich. Where they do fault them is when it starts affecting them.

Key takeaways from Part 8:

-

Being moderate is not at odds with criticizing the establishment, the status quo, or corporate interests.

-

Criticizing the establishment is not a substitute for taking positions voters agree with on the issues they care about.

-

For a more detailed analysis of what it does and does not mean to be a moderate, see here.

Part 9: Lessons from the Biden Years

To move forward, we need to take an honest look at mistakes our party made in the last four years. Part 9 examines what we see as the major political lessons of the Biden era, including:

Inflation9.1

Voters hated inflation and blamed the Biden administration for it. Inflation was likely the single largest factor in Democrats' 2024 defeat. However, while inflation is essential to understanding what happened in 2024, it can't explain everything about the election—or the longer-term trends we saw in Part 1.25

Immigration9.2

Immigration is an important issue to voters, and the Biden administration's approach to immigration during the first several years of the administration was highly unpopular. This likely cost Democrats electorally in 2024.

Biden's decision to run9.3

President Biden's decision to run for reelection was a disastrous mistake.

Talking about democracy vs. talking about the economy9.4

Democratic norms are under threat from the Trump presidency. But messaging focused on the threat Trump and other Republicans pose to democracy was less persuasive to voters in 2024 than messaging focused on concrete economic policies. Further, polling from The New York Times shows that voters see Democrats as overly focused on democracy, at the expense of being insufficiently focused on issues like the cost of living.

Reproductive rights9.5

Abortion rights are popular, and efforts to restrict abortion lead to political backlash. With that said, voters see the Democratic Party as putting too much emphasis on abortion, particularly relative to issues like the economy and the cost of living.

Key takeaways from Part 9:

- Most importantly: Inflation and immigration hurt Democrats in 2024.

Part 10: The New Politics of Evasion

Since November, a number of hypotheses have emerged as to why Democrats struggled in the 2024 election. This section examines a few prominent hypotheses, including theories that pin the blame for Democrats' losses on Kamala Harris's "moderate dream" campaign, the legacy media, Democrats' use of academic language, the impact of social media, and an insufficiently left-wing Democratic economic platform. We find that while some of these accounts contain kernels of truth, they all fail to fully explain Democrats' recent electoral failures.

But didn't Kamala Harris run a "moderate dream" campaign and lose?10.1

Harris did try to moderate during her abbreviated presidential campaign. While she lost the election, her pivot to the center coincided with a significant increase in her approval rating—reason to be skeptical that her efforts to moderate cost her electorally.

More importantly, despite her attempts to moderate, most voters still saw Harris as too liberal. Her attempts to moderate met with limited success primarily due to her:

-

Record of advocating for very liberal policy positions throughout her career.

-

Close association with a president whom the overwhelming majority of Americans disliked and thought was too left-wing.

-

Explicit refusal to break with President Biden on any major issues.

Harris's campaign is a reminder that being moderate is not something that Democratic candidates can just "turn on" during campaign season. We cannot expect to position ourselves and/or govern as progressives, flip to being moderate during an election, and successfully convince voters that we sincerely hold moderate views and policy positions.

Legacy media is less powerful than ever, and the people who work in it and consume it are members of the demographic groups that have most swung toward Democrats since 2012. Blaming The New York Times and its electoral coverage for Democrats' struggles in 2024 does not hold up to scrutiny.

Democrats lost the social media battle in 2024, likely costing our party electorally. Increasing our side's share of voice on platforms like TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and X, where a rapidly growing number of voters get their news, will be important for Democrats going forward.

With that said, theories that claim Democrats can win again merely by improving our "pipes" for delivering our message to voters—without shifting our prioritization or our positioning—overstep the evidence. Ultimately:

-

There is no way to disentangle Democrats' struggles on social media from our party's struggles—for substantive reasons—among the types of voters who get their news from social media.

-

Theories of the 2024 election that hinge on social media dynamics fail to reckon with the variations in performance among congressional Democrats. Electoral overperformance among Democratic candidates was correlated with more moderate positioning, not with more popularity on TikTok.

-

In fact, when we look across all 2024 Democratic congressional candidates, the relationship between total social media following and candidate performance relative to expectations is actually slightly negative, as the chart below shows.

Trying to compete more on social media is a good idea for our party, but establishing that goal does not answer the question of what Democrats should say to the low-engagement voters who get their news from social media platforms like TikTok.

For example, in the aftermath of the 2024 election, much was made of whether Kamala Harris should have gone on Joe Rogan's podcast. The less frequently asked—but more important—questions are: Had Harris gone on Rogan, what would she have said? How would she have responded to difficult questions about inflation, the border, crime, or culture-war topics? How would her message have been received by Rogan's audience?

Ultimately, the best answer to how Democrats should approach social media is that we should use these platforms to talk about popular positions on the issues voters care about most.

Blaming language10.4

Democrats would likely benefit from using less jargon from academia or the world of progressive advocacy groups. But merely changing the words we use will likely not be sufficient if we do not also change our unpopular positions and shift our prioritization.

Blaming an insufficiently left-wing economic agenda10.5

In this section, we examine whether Democrats can win back working-class voters by running on a more left-wing economic agenda than the party currently endorses. In our view, the left-wing economic populist argument gets some things right and some things wrong. In particular, we argue for a distinction between:

Emphasis: We think Democrats should place more emphasis on economic issues, like lowering costs and ensuring economic fairness, in our agenda and communications. This also means placing less emphasis on issues that working-class voters do not see as priorities, like climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural concerns. Here, we should look to politicians like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for guidance. Their focus on the Trump administration's efforts to cut taxes for the rich while gutting health care for low-income Americans during their "Fighting Oligarchy" tour shows how Democrats should approach prioritization. We need to focus relentlessly on attacking Republican policies to help the rich and promoting our own policies to help the middle class.26

Substantive positioning: Many Democratic economic policies are popular, but some are unpopular. Democrats should campaign on popular economic policies that would help lower-income and middle-class families regardless of whether the policies come from the "progressive" or "centrist" wing of the Democratic Party. But we also need to avoid campaigning on unpopular economic policies, regardless of whether or not the policies code as "centrist" or "progressive." That means avoiding unpopular centrist positions like former Democratic Senator Kyrsten Sinema's opposition to prescription drug pricing—but it also means avoiding unpopular progressive positions like student loan forgiveness.27

Emphasizing economic issues in our messaging is also not enough. Talking more about the economy will not prevent Democratic candidates from being attacked on issues where our stances are unpopular, like immigration, public safety, energy production, and cultural issues. Defusing attacks on these topics will require more than trying to change the conversation: It will require adopting more popular—and more moderate—stances on these issues. This shift should happen in concert with increasing our focus on economic issues.

Key takeaways from Part 10:

-

While some of these hypotheses contain kernels of truth, they all have flaws, and none are sufficient to explain our party's struggles.

-

Rather than avoid examining the role our party's positioning and prioritization played in our defeat, we should be addressing these problems head on.

Part 11: Looking Ahead

The terrain that the campaigns of 2026 and 2028 will be fought on is not yet settled, and will depend in large part on decisions the Trump administration and congressional Republicans make in the next several years, as well as on domestic and world events. Nonetheless, the evidence in the prior sections demonstrates that in a wide range of possible circumstances, Democrats would benefit from adopting more popular stances on issues where our views are unpopular. The issues where our party needs to moderate will almost certainly continue to include immigration, public safety, energy production, and some identity and cultural concerns. Democrats should also focus more on issues voters do not think we prioritize enough—particularly the economy and the cost of living—and should focus less on issues voters think we overemphasize, like climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues.

In addition, Part 11 discusses several other key strategic choices that Democrats should make, including our messaging about the Biden administration, strategies for fighting the Trump administration, and the importance of recruiting candidates who have a track record of heterodoxy, moderation, and electoral overperformance.

Democrats should break with the Biden administration11.1

The Biden administration had a number of significant legislative accomplishments, but voters did not see his administration as a success. Democrats should distance ourselves from the Biden administration, particularly by critiquing the Biden administration's approach to border security and the cost of living.

Democrats should be disciplined and strategic in which fights we pick11.2

Deciding to win does not mean Democrats should cave to the Trump administration. We should vigorously oppose the Trump administration—but we should also be disciplined and strategic about how we do that. We should focus our opposition to Trump on issues where voters are most on our side, like tariffs, Medicaid cuts, and tax cuts for the wealthy, rather than on issues where voters distrust us, like immigration.

The importance of recruiting heterodox candidates in 202611.3

Just as we did in 2006, Democrats should nominate candidates who break with progressive orthodoxy for competitive 2026 congressional races. This is particularly important in the Senate, where winning a majority requires victories in states where conservative views dominate, such as Iowa, Nebraska, Texas, Kansas, and Alaska. In some deep-red states, Democrats should also consider stepping aside to let candidates who are not officially affiliated with the Democratic Party run head-to-head against Republican nominees.

What Democrats should look for in our 2028 presidential nominee11.4

Our party needs to be thoughtful about whom we nominate in 2028. When considering candidates, we should look closely at their:

- Electoral track record: When considering candidates who have already run for office, Democrats should pay close attention to whether they overperformed or underperformed the national ticket in their previous races. The table below shows how potential 2028 Democratic hopefuls performed, relative to expectations, in their most recent elections.28

We should also look closely at their:

-

Current issue positions: Candidates who take popular positions on issues that are important to voters—including economic policy, immigration, public safety, energy production, and some identity and cultural concerns—are more likely to be strong general election candidates.

-

Past history of position-taking: In 2024, Kamala Harris's attempts to moderate were undermined by positions she had taken during previous campaigns. The 2028 Democratic nominee will do worse if their attempts to run on a common-sense, popular agenda are at odds with a history of unpopular position-taking.

-

Deciding to Win: Democrats should pick a nominee who understands what it takes to win elections in difficult terrain—and is willing to run on positions that majorities of Americans support, even if this sometimes requires breaking with the unpopular demands of progressive advocacy organizations, corporate interests, or the Democratic donor class.

Now that our coalition is the high-turnout one, Democrats also need to avoid concluding that strong results in special elections or the 2026 midterms mean that the 2028 election will be an easy one. The less-engaged voters whom we have lost in recent years are less likely to vote in midterms or special elections but will likely return in 2028. As we saw between 2017 and 2024, doing well in midterms and special elections does not guarantee Democrats anywhere close to the same results in a presidential race.

Reasons for optimism11.5

The extreme agenda of the second Trump administration has already turned off many voters who wanted low prices and a secure border, not cuts to Medicaid, trade wars, and tax cuts for the rich. If Democrats are disciplined, strategic, and willing to focus on voters' top priorities and to moderate on key issues, we have a strong chance of taking back Congress in 2026 and the White House in 2028.

Key takeaways from Part 11:

- While Democrats struggled in 2024, there are reasons for optimism going forward. Our party will be best positioned to win in 2026 and 2028, however, if we nominate candidates whose views and priorities align with the electorate.

Conclusion

"Hope is not blind optimism… Hope is that thing inside us that insists, despite all the evidence to the contrary, that something better awaits us if we have the courage to reach for it and to work for it and to fight for it."

— Barack Obama

To win elections, Democrats need to make the following changes. First, we need to focus more on the issues voters do not think we prioritize enough (the economy, the cost of living, health care, border security, public safety), and focus less on the issues voters think we prioritize too highly (climate change, democracy, abortion, and identity and cultural issues). Second, we need to moderate our positions on issues where our agenda is unpopular, including immigration, public safety, energy production, and some identity and cultural issues.

We must also do a better job of listening to and appealing to voters' frustrations with the political establishment, including by leaning into critiques of political corruption and the outsized power of lobbyists, corporations, and the ultra-wealthy. But we must understand that criticizing the status quo is a complement to advocating for popular policies on the issues that matter most to the American people, not a substitute.

It is essential that we make these strategic shifts because it is essential that we win. If we cannot win, we will be unable to prevent the disastrous impact of Republican policies or improve the lives of all Americans.

But winning does not happen by accident. Winning is a choice—a choice to be disciplined and strategic and to be willing to confront difficult truths about the electorate.

We must make this choice. The stakes are too high for us to do anything less.

About the Authors

Simon Bazelon is a Research Fellow at Welcome, where he focuses on data analysis and political strategy.

Simon previously worked as a Research Analyst at Future Forward, Blue Rose Research, and Data for Progress, where he helped develop messaging guidance for Democratic candidates, PACs, and advocacy organizations.

During the 2024 election cycle, he helped write "Doppler," a weekly memo for Democratic political operatives examining what campaign messaging was most effective.

He holds a bachelor's degree from Yale University and lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

Lauren Harper Pope is a Welcome Co-Founder working to depolarize American politics through work with Welcome PAC, The Welcome Party (c4), and The Welcome Democracy Institute (c3).

Before co-founding Welcome, Lauren served as South Carolina State Director for Beto O'Rourke's presidential campaign, as Policy and Communications Advisor for Columbia, South Carolina Mayor Steve Benjamin, and as an aide to former South Carolina state Sen. Mia McLeod.

Lauren leads the coordinated (hard side) program for Welcome PAC. In 2024, Welcome supported a slate of nine moderate Democrats in conservative-leaning congressional districts across the country, including three Blue Dog caucus co-chairs.

Lauren hosts The Depolarizers podcast, where she and guests discuss ways to effectively depolarize American politics, and she writes at WelcomeStack.org.

Lauren is an alumna of the University of South Carolina. She lives in the Charlotte metro in Indian Land, South Carolina.

Liam Kerr is a Co-Founder of Welcome PAC, The Welcome Party (c4), and the Welcome Democracy Institute (c3).

Before co-founding Welcome, Liam previously served as Massachusetts State Director for Democrats for Education Reform, an advocacy group that supports Democratic candidates who are working to improve our nation's public education system.

Liam graduated from Providence College and the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. He lives in Needham, Massachusetts.

Notes for the Reader

This report is an abridged version of the full Deciding to Win report (352 pages). To request a briefing from the authors on the full Deciding to Win report, click here. To contact the authors, reach out at contact@decidingtowin.org.

While we extensively fact-checked Deciding to Win in order to ensure accuracy, it is always possible that mistakes remain. We encourage any readers who notice factual errors to reach out to us at factchecking@decidingtowin.org. Mistakes will be corrected as quickly as possible, and any changes will be noted in the text.

All numbers and figures are accurate as of September 27th, 2025.

Sources

Empirical claims in Deciding to Win that are based on publicly available evidence are accompanied by a hyperlink to evidence supporting the claim. In addition, a traditional bibliography can be found here, and more data is provided in the Appendix below.

We supplemented the publicly available data we cite by surveying more than 500,000 Americans. We conducted these surveys between November 13th, 2024, and June 18th, 2025. All surveys were conducted via online web panels. While we are grateful to Blue Rose Research for collecting this data, their role was limited solely to that of a data vendor and should not be taken to imply their endorsement of any of the claims made in this report.

Appendix

Written Supplementary Materials:

Additional Data:

-

Changes in Cosponsorship Rates Among Congressional Democrats on Select Bills

-

Perception of the Democratic Party, 2012-2025

-

Perception of the Republican Party, 2012-2025

-

Frequency of Select Words, 2012 and 2024 Democratic Party Platforms

-

Perception of Joe Biden, 2019-2024

-

Perceptions of Recent Presidential Nominees (1960-2024)

-

Polling Error in Presidential Elections Since 1960

-

Changes in Democratic Vote Share by Race, Education, and Ideology, 2012-2024 (CES)

-

2024 House and Presidential Results Correlation (Contested Races Only)

-

2024 Senate and Presidential Results Correlation (Contested Races Only)

-

Democratic Special Election Overperformance, 2023 and 2024

-

Issue Salience and Party Trust Data

-

2024 House Candidate Performance Relative to Expectations by Attribute

-

Correlations in Policy Support Across Demographic Groups

-

Full Issue Polling Results

-

Incumbent Senate Democratic Candidate Performance Relative to Expectations by Attribute (2020-2024)

-

Incumbent Senate Republican Candidate Performance Relative to Expectations by Attribute Analysis (2020-2024)

-

Issue Positioning and Candidate Performance Relative to Expectations, Part 1

-

Issue Positioning and Candidate Performance Relative to Expectations, Part 2

-

Performance Relative to Expectations vs. Social Media Following, 2024 Democratic Congressional Candidates

-

More Modest Democratic Economic Policies Tend to Be More Popular

-

Correlation Between Repeat House Candidate Performance Relative to Expectations in Consecutive Elections

-

Performance Relative to Expectations in Most Recent Election Among 2028 Democratic Hopefuls